Data suggest that more universities ŌĆō and subject areas ŌĆō will need to succeed on the world stage to sustain the countryŌĆÖs rise

Source: Getty

An announcement last month by the Chinese government about which institutions will be included in its latest funding initiative to create ŌĆ£world-classŌĆØ universities may have pricked up the ears of the elite Western institutions that dominate higher education rankings.

ChinaŌĆÖs two most consistently highly ranked institutions ŌĆō Peking and Tsinghua universities ŌĆō are already threatening the top 20 of Times Higher EducationŌĆÖs World University Rankings and the ŌĆ£Double First ClassŌĆØ project, which will target funding at 42 institutions, could help more academies become household names worldwide.

But is this focus on elite Chinese universities, when there are estimated to be more than 2,000 higher education institutions in the country, a sustainable strategy in the long term?

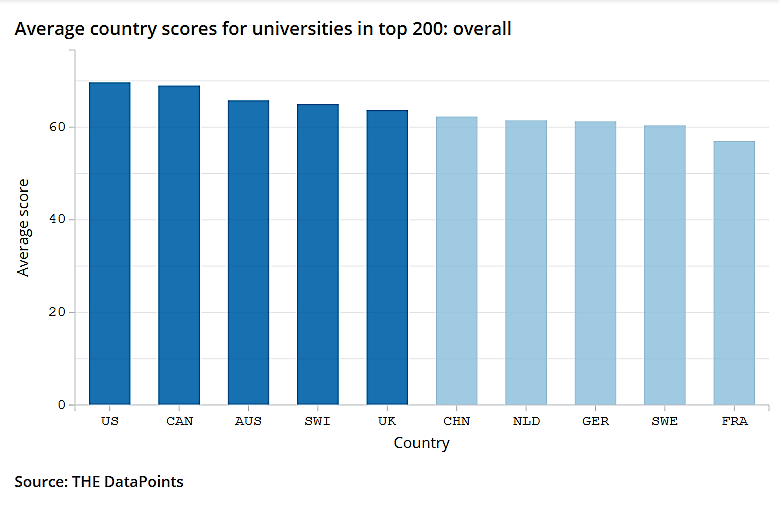

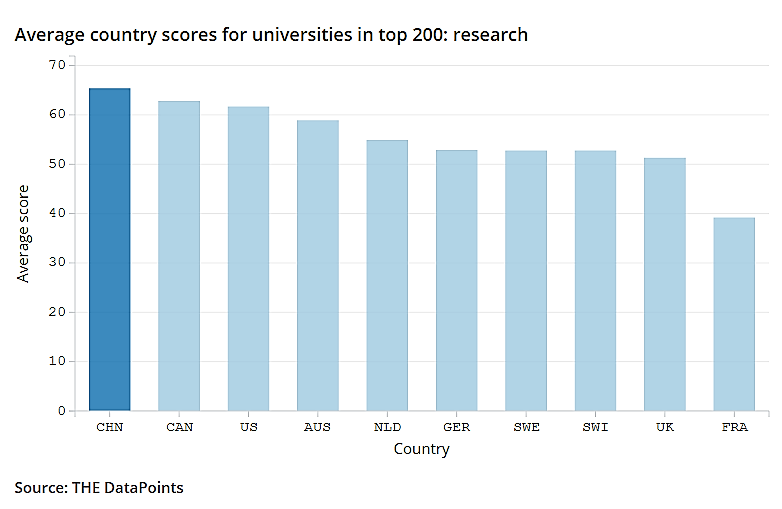

An idea of the challenge facing the country can be seen by looking at the average scores for Chinese universities in the THE rankings compared with other nations.

Using the average for universities that make the top 200 shows that ChinaŌĆÖs elite universities are competing well with the rest of the world: China is sixth on overall score in the list of 10 nations that have more than five universities at the top end of the World University Rankings. Indeed, ChinaŌĆÖs elite have the highest average score of any country in three of the five pillars in the rankings: teaching, research and industry income.

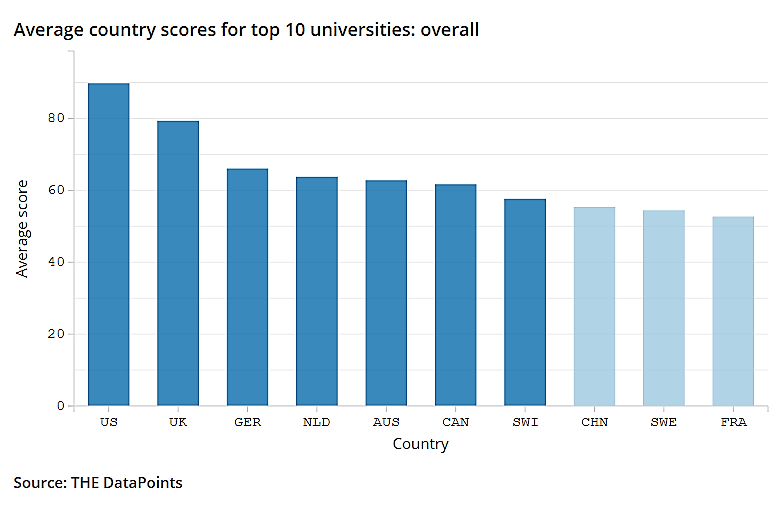

However, taking the top 10 universities from the same countries across the whole ranking (more than 1,000 institutions in total) shows how the US still dominates and that countries such as China tail off (it is eighth in the list) because only a few of its institutions are at the top end of the rankings.

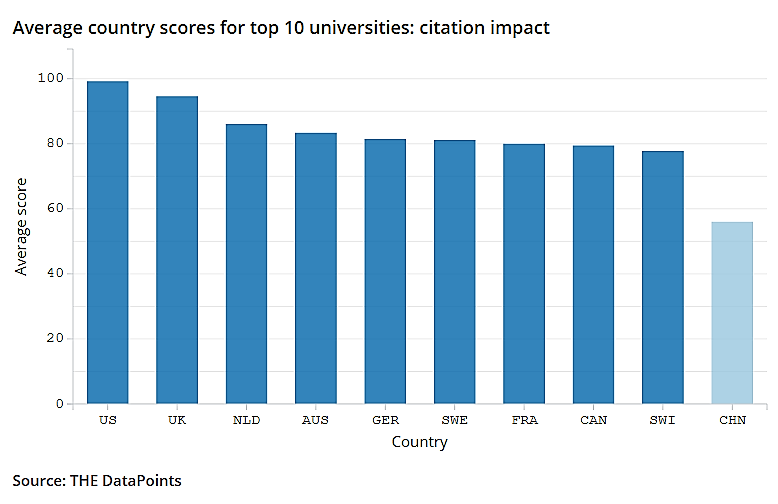

Notably, using this approach, China still leads the world on industry income but has huge ground to make up on citation impact, with an average score of 56 out of 100 for its top 10, more than 20 points behind its nearest rival in the list, Switzerland.

THE data scientist Billy Wong said that ChinaŌĆÖs performance in the rankings ŌĆ£needed to be seen in the context of where the Chinese government is targeting its funding, which is invariably at the elite end of higher educationŌĆØ.

He added that it was possible that the country required ŌĆ£a much more comprehensive strategy if it is to truly compete with countries [such as] the US in the futureŌĆØ.

So what would a more comprehensive higher education strategy in China look like?

Marijk van der Wende, professor of higher education at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, said that in her view it was important to turn the issue ŌĆ£90 degreesŌĆØ and examine whether China was being too narrow in terms of the research disciplines it was targeting rather than the types of university.

Research that she is currently working on highlights how Chinese universities dominate subject rankings in several applied science disciplines such as engineering but are relatively absent from other subjects, particularly in the humanities or social sciences.

ŌĆ£I would be more concerned about the breadth of their strategy. I know why they do it, because these are the areas that are important for ChinaŌĆÖs economic development,ŌĆØ said Professor van der Wende.

She added that she also wondered if humanities and social science academics ŌĆ£have the same conditions to work in as the science and engineering people and how this affects collaboration towards more interdisciplinary workŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£My concern is that with this narrow strategy you get to the top [of rankings] very fast, but what does it mean for the development of ChinaŌĆÖs universities as comprehensive universities?ŌĆØ she asked.

Professor van der Wende said that it was possible China was ŌĆ£challenging the assumptionsŌĆØ in the West about what makes a world-class university, by indicating a model with ŌĆ£Chinese characteristicsŌĆØ.

However, she pointed out that it was not only China that was finding success through concentrating on applied science; universities in the US and Europe that had a ŌĆ£strong technological coreŌĆØ and worked closely with industry also tended to do well in rankings, although such institutions did connect this to specific areas in the social sciences and humanities.

It had also led other institutions to focus more on this area ŌĆō for example, Harvard UniversityŌĆÖs major investment in, and expansive new campus for, its John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Lili Yang, a doctoral student at the UCL Institute of EducationŌĆÖs Centre for Global Higher Education who is working on a major project comparing ChinaŌĆÖs higher education system with France, the UK and Japan, also pointed out that the countryŌĆÖs rapid progress ŌĆ£is mostly driven by natural sciences and engineeringŌĆØ and that it would take time for other disciplines to reach the same level.

But she said that in terms of ChinaŌĆÖs drive in applied science, there was still a lot of room for it to rise up the global rankings without necessarily needing to compete in other disciplines.

ŌĆ£There is still a large space for progress as most elite universities in China still cannot be called world-elite universities ŌĆō they still need time and continuing investment to let more of them enter the world-elite university family,ŌĆØ said Ms Yang.

She also said that unlike previous excellence initiatives, the new Double First Class strategy did include some money for institutions in poorer provinces, while the role of local government was sometimes forgotten.

ŌĆ£Beyond the newly announced ŌĆśworld-classŌĆÖ strategy issued by central government, many local governments including those in relatively poor provinces have also issued their own ŌĆśworld-classŌĆÖ strategies.

ŌĆ£Local strategies not only support elite universities but also second-tier universities in their own provinces,ŌĆØ she said.

Source - THE