Chinese manufacturers once bought high-tech materials from overseas firms. Rising expertise means they now shop locally, altering global trade

By ANJANI TRIVEDI Updated Oct. 18, 2016

ZHUHAI, China— Judah Huang works deep in the global supply chain at a Chinese company that makes nonstick coatings for cookie sheets, frying pans and grills sold in stores such as Wal-Mart.

Until a few years ago, the pans and griddles were made in China, but most of the materials that went into them were not. Mr. Huang imported most of the resins, pigments and pastes for his coatings from multinational suppliers such as Dow Chemical Co. of the U.S. and Eckart Effect Pigments of Germany.

Now, in a shift that is echoing throughout China’s vast manufacturing sector, he is buying more than 70% of those things from local suppliers.

“All these raw materials, now somebody in China makes it,” says Mr. Huang, chief technical manager of GMM Non-Stick Coatings, which has a factory in this city near Macau.

China, long the world’s factory floor, is taking control of a bigger portion of the world’s supply chains as well, causing a shift in global trade patterns by buying less from abroad.

The No. 2 economy after the U.S. pulls in huge volumes of raw materials and components, from aluminum to microchips, which it fashions into finished products such as iPhones and George Foreman grills for sale around the world. Those supply flows turbocharged global trade for years and made China one of the top export destinations.

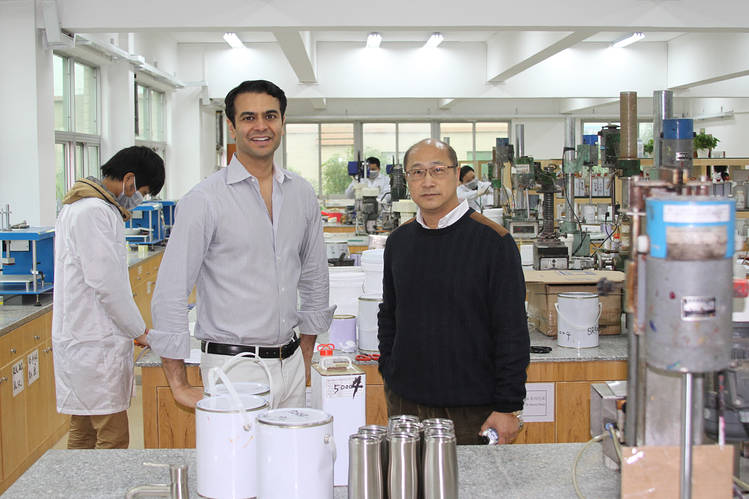

GMM technicians discuss nonstick coatings the company makes for cookie sheets, frying pans and grills sold in stores such Wal-Mart. PHOTO: CHAO DENG/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Now those flows are shrinking, which is pummeling China’s trading partners, slowing global growth and providing further ammunition for politicians including Donald Trump who question the benefits of global trade.

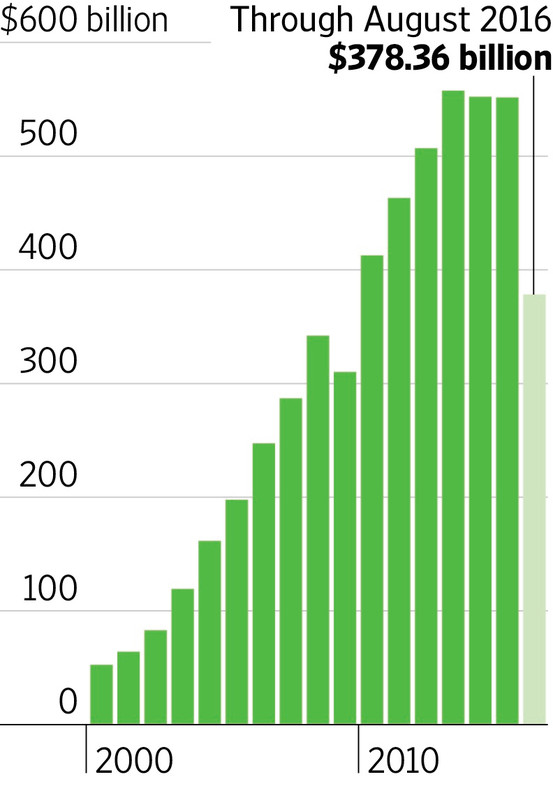

Exports to China, which had risen nearly every year since 1990, fell 14% last year, the largest annual drop since the 1960s. They are down another 8.2% this year, through September. The decline helped shave 0.3 percentage point off world trade growth last year, and is a big reason that growth is expected to slow to 1.7% this year from the 5% a year it has averaged over the last two decades.

China’s trade surplus with the U.S. hit a record last year, largely because China is buying less and because global commodity prices fell.

Some of that decrease is the result of economic slowdown and a glut of goods—in China and globally. But China also is increasingly turning inward for its manufacturing needs, pushing to substitute local inputs for foreign, especially in plum, high-margin areas such as semiconductors and machinery.

That is disturbing for many global manufacturers, which have ceded low-end production to Chinese rivals but are banking on staying ahead in higher-end goods and ingredients that feature more advanced technology.

“The very high end is still not there,” says Ka Lok Cheung, head of operations in Zhuhai for Germany’s Eckart, noting that local rivals still have trouble maintaining consistent quality in some hard-to-make pigments. “But for many things, they’re really catching up.”

How Chinese Manufacturers Are Changing Global Trade Flows

Chinese manufacturers are buying more raw materials and components from domestic suppliers, taking a chunk out of imports from multinational companies. The push to use local inputs for manufacturing is spreading to higher-tech items and contributing to slower global trade growth.

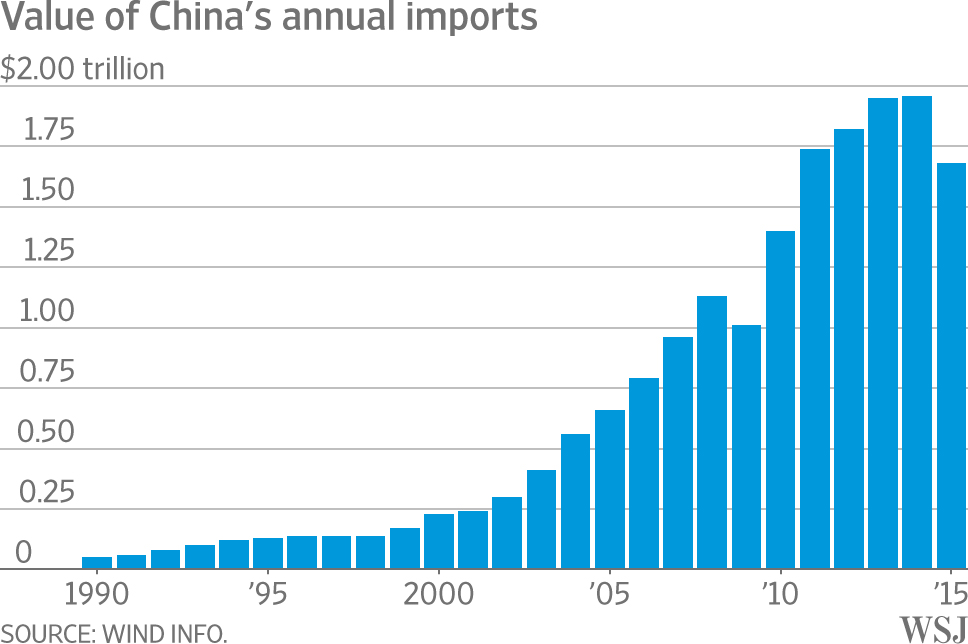

1. Value of China's annual imports

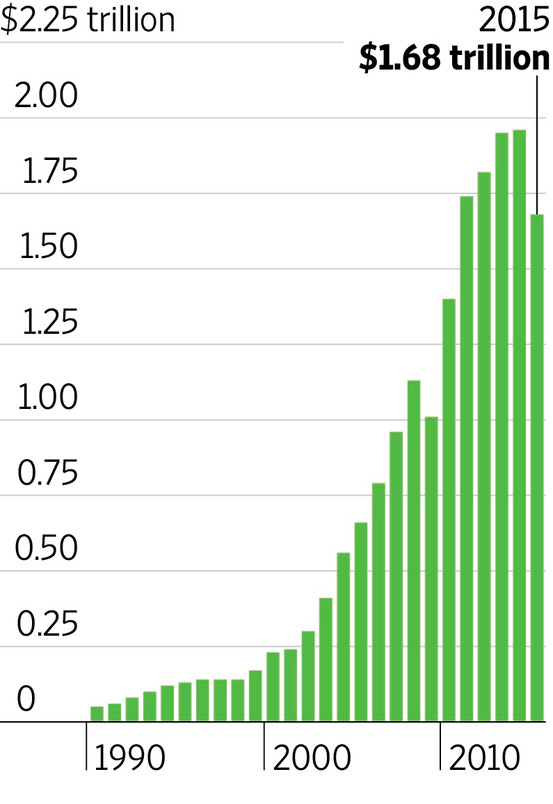

2. Portion of foreign inputs in China's exports

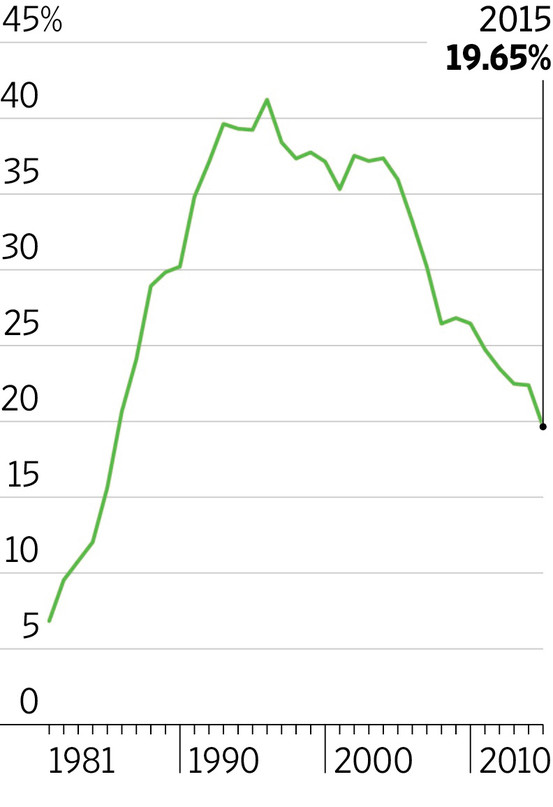

3. Annual value of China’s high-tech and new-tech imports

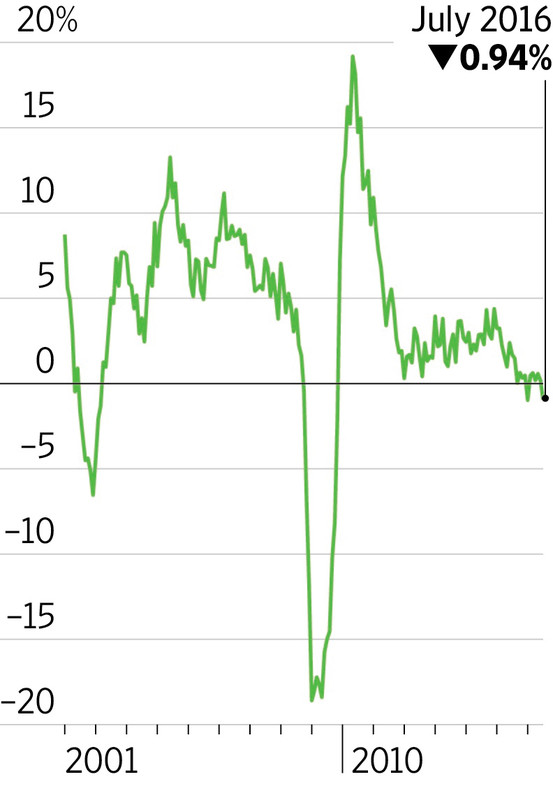

4. Change from previous year of World Trade Monitor index

Sources: Wind Info. (imports); CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (index)

The value of components and materials imported by China for use in other products fell 15% last year from the prior year, the largest annual decline since the global financial crisis, and it dropped another 14% in the first nine months of this year, according to Wind Info, a Chinese data provider that uses official Chinese customs figures.

Part of that decline is because Chinese exporters have been using less of those imports in their goods, data from an International Monetary Fund study suggests. The proportion of foreign-made inputs in Chinese exports has been shrinking by an average 1.6 percentage points a year over the past decade, and last year fell to 19.6%, from more than 40% in the mid-1990s, according to Chinese trade data.

Woodridge, Ill.-based Wilton Brands, which makes baking pans in China that use GMM’s nonstick coating, previously used steel from Japan or South Korea because Chinese steel had too many flaws, says James Hill, executive vice president of global operations. With improvements in Chinese steel, the factories now buy locally, which means that almost all of the pan, including the ingredients for the coating, is now produced in China, he says.

For low-end products, especially in sectors that have suffered from overcapacity, China’s Ministry of Commerce has levied antidumping tariffs against companies such as Dow Chemical and Eastman Chemical Co. that it views as undermining local industry by unloading goods in the country at too cheap a price.

Dow Chemical declined to comment on the tariffs but said it has sold the business that was affected and focused on higher-end chemicals. Those now account for more than 95% of its revenue in China, says Peter Wong, the company’s president for Asia Pacific. Eastman declined to comment.

China’s GMM Non-Stick Coatings has begun buying more materials from domestic rather than multinational suppliers. Workers at its factory in Zhuhai, China. PHOTO: VINCENT YU/ASSOCIATED PRESS

To build domestic capabilities on the high end, the Chinese government last year announced a plan to raise the domestic content of core components and key materials to 40% by 2020 and 70% by 2025. It has been spending large amounts on research and development: $213 billion last year, or 2.1% of gross domestic product, according to state media reports. In June it pledged more money for “technological innovation.”

Biotechnology, aerospace and other high-tech-related exports to China fell 5% this year through September, compared with the same period last year, according to Wind Info, extending a two-year decline.

In specialty or higher-end chemicals—GMM’s industry—the amount China imports from the U.S. fell 8% in the first seven months of this year.

GMM was founded nearly a decade ago by U.S. chemical-industry veteran Ravin Gandhi and his Hong Kong business partner Raymond Chung, one of a wave of manufacturers attracted by China’s huge, cheap labor force and growing network of factories. GMM’s plant produces 20 metric tons of coatings each day, enough to stick-proof around 600,000 cooking pans or 200,000 electric grills.

For years, GMM acquired more than half of its raw materials from chemical giants such as DuPont Co. and Dow Chemical, with which DuPont is merging. It imported all of its two most important types of ingredients—silicone resins and aluminum paste, tricky, high-margin chemicals that Chinese suppliers weren’t able to make. GMM’s purchases in China tended to be lower-end ingredients such as solvents, which were easy to make and dangerous to ship.

The global recession and demand slowdown that started in 2008 pummeled chemical sales and worsened a supply glut. Chinese chemical factory utilization rates dropped sharply between 2008 and 2014, a sign of slack in the industry. China’s chemical makers, whose profits were getting squeezed by overcapacity and falling prices of cheaper ingredients, accelerated their push into higher-value areas.

Around 2012, salespeople from Chinese chemical makers started showing up at GMM with five-gallon buckets of resins and higher-end pigments that cost much less than their imported counterparts and passed the rigorous quality standards required by regulators such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, says GMM’s Chicago-based CEO Mr. Gandhi. GMM’s customers were pressing for cheaper prices and a wider variety of colors and features, such as smoother pan surfaces.

GMM started shifting purchases to local firms. Until last year, GMM bought silicone-based fluids for its coatings from Dow Corning. In 2015, it shifted much of its business to a local Chinese supplier.

Because domestic suppliers are 10% to 20% less expensive than foreign ones, says Mr. Huang, who previously worked for a German industrial-coatings company, the shift has been a “game-changer” for GMM. It has cut the cost of finished coatings by 10% from 2012, raising the company’s profit as much as 15% and allowed price reductions for customers. More than 70% of GMM’s 200 vendors are now based locally, compared with 40% five years ago, Mr. Gandhi says.

Dow Corning declined to comment.

GMM co-founders Ravin Gandhi, left, and Raymond Chung in one of the company's research laboratories. PHOTO: GMM

One local producer whose chemicals GMM now uses is Fujian Kuncai Material Technology Co. Ltd., a maker of shiny pigments and aluminum paste based in Fuqing. After initially plying its wares to small industrial paint shops in China’s southern manufacturing zone, it increased investment in new products, set up a big R&D center in China and started working with Chinese universities to hone its technological edge. A year and a half ago, it formed a joint venture with a Netherlands-based distributor to sell its China-made pigments in Europe.

GMM now buys blue, silver-white, gray and copper-colored pigments from Fujian Kuncai rather than import them, says Mr. Huang. The pigments cost as much as a quarter less than the cost of an equivalent import, he says.

Around 10 miles from GMM’s Zhuhai factory, at the headquarters of German pigment maker Eckart’s main China unit, Mr. Cheung, the operations chief, says competition with local manufacturers is getting more intense.

“They really want to chase us,” he says. “They see the market demand is increasing for this better product.”

Eckart sells aluminum pastes to GMM. Five years ago, GMM imported those pastes from Eckart’s German facilities; now it uses pastes Eckart recently started making for less in Zhuhai. While Eckart still makes those pastes from raw materials it imports from its German and U.S. facilities, it is looking to purchase more locally as well, Mr. Cheung says.

For its part, Dow Corning, a subsidiary of Midland, Mich.-based Dow Chemical, is fighting back with lower-priced offerings that are only sold in China, says Dow Corning’s Greater China President Jeroen Bloemhard.

The company is looking for more opportunities to source domestically, particularly as it vies to supply China’s domestic market. “Fundamentally, there will be a preference to buy locally if it is actually possible,” he says. - WSJ

—Chao Deng contributed to this article.