Government’s push to put science and technology at forefront of nation’s development is creating new breed of highly-paid scientific academics

Top scientists are offered lucrative packages to return to China from overseas to carry out their research. Photo: Reuters

They may be small in number and keep a low profile, but the ranks of millionaire scientists in China are growing and they are leading the nation’s rise as a global power in scientific research.

This new breed of scientist works in state-of the-art laboratories and are increasingly carrying out groundbreaking research published by top international scientific journals such as Science or Nature.

China is now the world’s second largest contributor to high-quality scientific research papers, right behind the United States, according to the Nature Index 2016 released last week.

“Of the top ten countries in the Nature list, only China has shown double digit growth between 2012 and 2015 with some of its universities growing their contribution to the index as fast as 25 per cent annually,” Nature said in its press release.

Better salaries and other financial benefits - thanks largely to the government largesse - help swell the ranks of China’s research teams.

The high rise in salaries for the small but growing number of China’s elite scientists has been relatively rapid.

The scientific journal Nature conducted a global survey of scientists’ salaries in 2010 and found the average Chinese scientist earned less than US$40,000 a year. Their counterparts in the United States, meanwhile, made an average of almost US$80,000.

Researchers and academics in China interviewed by the South China Morning Post suggest this picture has changed.

“The gap is vanishing,” said a senior life scientist at Tsinghua University in Beijing, one of the nation’s top research centres. “In major cities, more and more Chinese scientists are making as much as they can for the same position in the US,” he said.

The average annual starting salary for a professor returning from overseas to a major university in China is about 800,000 yuan (HK$955,000) a year, or more than US$120,000, according to a study by researchers at the Science and Technology Talent Centre under the Ministry of Science and Technology.

At some public universities scientists get a 700,000 yuan bonus for each paper published by top academic journals, according to the same study published in the magazine Chinese Science and Technology Talent in March.

The background to this increase in top scientists’ salaries is China’s enormous spending on research and development.

A total 1.4 trillion yuan was spent on the sector last year, according to the government, more than the entire GDP of New Zealand.

Most R&D funds were previously spent on purchasing hardware with salaries for staff considered less important. Now government leaders have decreed that attracting the best talent is more important.

These efforts to recruit the best minds and improve the quality of scientific research in China appear to be paying off.

The quality of research papers published by Chinese scientists has improved rapidly in recent years, according to the number of times their work is cited by other experts working in the field.

This is seen as a benchmark of the impact of a piece of research and citations for Chinese papers rank second only to the United States in sectors including material science, engineering technology, chemistry, agriculture and computer science.

Some Chinese scientists have become rich by exploiting the commercial potential of their research.

Professor Xu Man, a material scientist at the Wuhan Institute of Technology in Hubei, earned more than 13 million yuan last year by selling a ceramic coating technology to a company in Shenzhen, according to mainland media reports.

But many millionaires working in science have been created by the government and local authorities new found largesse, according to observers.

The “Thousand Talents” scheme launched by the central government in 2011, for instance, offered a one-off 1 million yuan bonus, with at least 3 million yuan in research funds, to successful applicants.

“Chinese scientists working in the world’s top research institutes are in short supply, but the demand for their return is almost infinite,” said Zhang Liyi, an official at the human resources department at the Ningbo Institute of Industrial Technology.

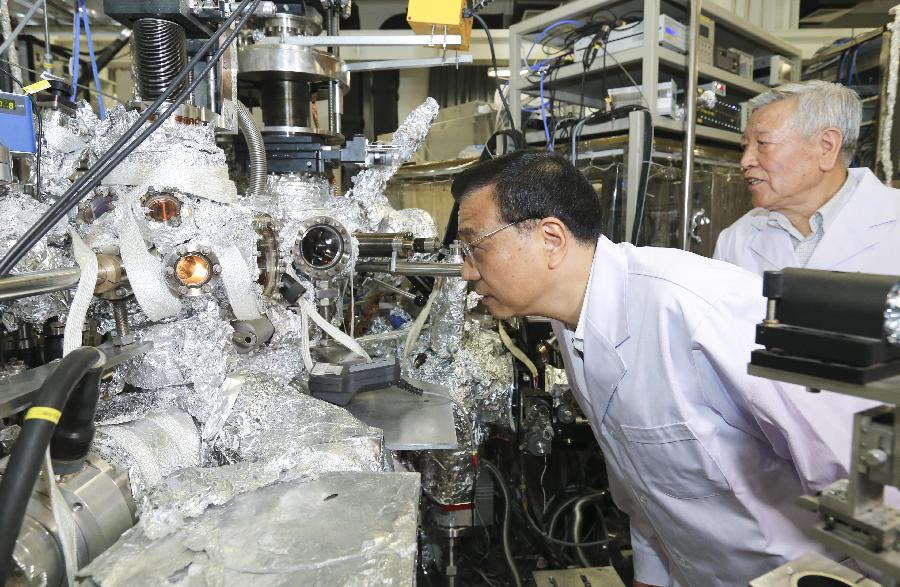

Premier Li Keqiang pictured visiting a laboratory in Beijing investigating electrical superconductors. Photo: Xinhua

A good Chinese scientist often received offers from several research institutes from the mainland, he said. “The competition can get tough.”

Zhang’s institute offered a package with up to 10 million yuan in research funds to attract a candidate, with the help of provincial and central government cash.

“It is difficult to attract high quality talent without a globally competitive package to offer,” he said.

Chinese researchers working in applied sciences such as computers, health and material sciences are the biggest earners, according to experts. Staff in the pure sciences earned less, they said.

High salaries and other perks are succeeding in luring top researchers home, but issues still remain.

High salaries and other perks are succeeding in luring top researchers home, but issues still remain.

Environmental problems such as air pollution and food safety ranked top among the concerns of Chinese scientist working overseas, said experts interviewed by the Post.

Scientists were also worried about government bureaucracy and interference in their work, the experts said.

The high pay and bonuses increasingly on offer to top scientists in China also do not reflect the reality faced by most researchers on the mainland.

The majority struggle with modest paychecks to deal with rising living costs, such as food and housing.

An entry-level scientist without overseas experience earned only 7,000 yuan per month in a government research institute in Beijing, according to a report by the People’s Daily last year. More than half of their salary is likely to go on rent, the article said. The traditionally low income of scientists in China has previously fueled the brain drain to the West.

This gulf between top earning scientists and their lesser-paid colleagues can also create resentment, according one researcher.

Becoming a millionaire on campus was like “walking on thin ice”, said the biologist working at Tsinghua University. The number of “super-rich” colleagues was increasing, but most kept a low profile because they did not want to antagonise their lower paid co-workers, he said.

A researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Policy and Management also warned of an increasing divide between rich and relatively poor researchers.

High salaries played an important role in China’s fight against other nations to retain its top scientific talent, but it could also widen the income gap and trigger conflicts within the research community, he said.

The government needed to address the concerns of high and low income scientists and ensure that both sides’ work was fully valued.

“The best scientists take academic freedom more seriously than money,” he said. “The Noble Prize tends to sidestep the highest paid.” - scmp

Related -